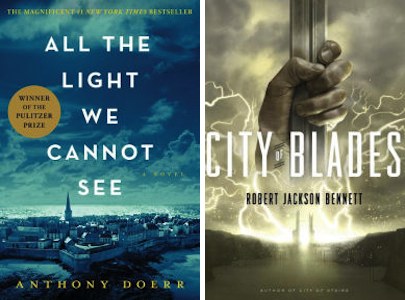

I went through a pretty odd experience this past fall. My brain had successfully split and was submerged in two fictional worlds at once—All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr and City of Blades by Robert Jackson Bennett. Many wouldn’t find this remarkable, but as a reader who laser-focuses onto whatever they’re reading, this was a very new experience. Not only that, but the two worlds I was occupying were seemingly fathoms apart. One was a devastated landscape that had gone through the hell of occupation and was trying to take that pain and turn it into something new and bolder, something brighter to light the way into the future. The other was France just before, during, and after World War II.

Hey, wait a minute . . .

Light spoilers for both novels.

I’m not pointing this out to be blithe or flippant. I was struck by the overlap because for all the grousing that’s sometimes done over the differences between genre versus non-genre fiction, for all the lines in the sand people like to draw against a surging and inevitable high tide, at the end of the day, all forms of literature are interested in the same thing: examining the world around us, interrogating our past while extrapolating our future, and using the narrative form to give a voice to what makes us human. And hopefully by the end of the story, no matter what world it’s set in, we’ll be better people.

While reading the two novels, I felt myself splitting, two pieces of myself becoming more and more invested in each fictional narrative. It was like looking across a gorge only to see myself holding a mirror, reflecting my own image back to me.

And man, these two books. These two books resonated—tuning forks set to similar frequencies of warfare, violence, pain, compromise, and bitter victory. All the Light We Cannot See is about Werner, a German boy indoctrinated into the Nazi Party, Marie Laure, a blind French girl fleeing Paris for St. Malo, and their connection across the war, the world, and after. City of Blades is about the bitter, cynical, and slightly idealistic General Turyin Mulaghesh trying to enjoy her retirement, but finding herself drawn into a Divine mystery in one of the most devastated cities of the War of the Continent—Voortyashtan, home of the Divinity Voortya, goddess of death, war, and pain. Already, you can see how these two works might relate to one another.

Both books feature characters (Werner and Mulaghesh) directly involved in committing atrocities, and each narrative forces them to see the pain they’ve caused, no matter what nationalistic fervor may have fueled it. Both explore the sheer enormity of these atrocities and how, when taken in large numbers, the horror of subjugation and death become too abstract a concept to grasp, so that such pain and destruction somehow feels inevitable, and unable to be stopped. Both writers are fascinated with resistance to such atrocious forces, and how to combat the aggressors on even the tiniest level through the use of code-breaking and secret transmissions in St. Malo, and Signe’s massive infrastructure project. Both novelists seem drawn to the idea that innovation and good will and hope can combat years of hatred, that the future can be built on the back of invention and finding ways forward, together. On an even deeper level, both books interact with the idea of mythology, self-made or not, and how the driving force of something immense in scope, that hopes to speak to you, can turn even the most rational person mad. Likewise, the appeal of choosing one’s own ideals, your own moral and human codes, man-made proclamations to hold oneself to a standard that is not implanted but rather, picked up, is equally important—and in fact, becomes one of the most important moments of each book, as heroes and villains alike must choose to embrace the power of detached violence, or the mantle of struggling ideals.

Let’s break it down. Soldiers first.

Werner, the German boy who from a young age is recruited for his brilliance with technology, is quickly indoctrinated into the Nazi Party. And how could he not be? The insidious narrative rings in his ears every day that his destiny is to take the world, that he’s the strongest, that he’s the best, that the rest of the world must be tamed, that if he works hard and acts without hesitation or mercy, he’ll get to eat; he’ll get to live. Even at his most vulnerable moments—when he hesitates, when he stops to question the cruelty he sees—he still doesn’t see himself slipping further and further into the Nazi mindset. He’s young, though that doesn’t excuse his actions; it only shows how easily one can be coerced under the right pressures.

Mulaghesh, on the other hand, is older when we meet her, and has already gone through hell and back. She wants to hide from a world she can’t quite hate, to escape the people that would use her, and to leave behind the past, when her youthful self fell under the sway of nationalist narratives and committed horrors. Through her, we see the effects of having already served: the bitterness, the PTSD, the pride of many moments and the shame at others. Mulaghesh began her service in her late teens (when she was Werner’s age), and the horrors she committed at that age burned themselves into her eyelids, so that she can’t even escape them when she sleeps. Through it all, however, she never loses the faint hope that a life of service can be more than war, than horror, than pain. That somewhere in the mess of emotion and violence is a noble effort to defend, serve, and protect people.

Both characters exist on the same spectrum, and represent the realities of warfare. You must live with what you’ve done, and though it can’t be forgotten, it can be looked in the eye and acknowledged. Werner slowly comes to see the humanity in those he’s been hurting, and his journey into the heart of darkness and out the other side is at the heart of his arc. In the epilogue of All the Light We Cannot See, there are instances of German characters aware of the heavy, awful legacy hanging on their shoulders, and even if they were nowhere near the Nazi party, that legacy persists. Likewise, Mulaghesh’s whole journey revolves around the purpose of being a soldier, and what that means in a society that is moving away from a certain national and religious identity. And she has to search out her purpose in the face of the commanding officer who ordered her down an atrocious path. War leaves scars. War weaves shrouds that never lift. Mulaghesh and Werner both have the scars to show and they certainly feel the weight of their shrouds. Their respective moves from complicity to rebellion, from owning up to atonement, provide the cornerstones of each novel.

Equally fascinating is the concept of resistance in each novel—and if not exactly resistance, then forging the way forward from war. In All the Light We Cannot See, Marie Laure flees from the occupation of Paris and finds refuge in her Uncle Etienne’s home on the island of St. Malo, the last Nazi foothold in France to fall at the end of the war. Uncle Etienne has severe PTSD from his time in World War I, but as Marie Laure becomes involved with the resistance in St. Malo, Uncle Etienne begins to realize that he must do something, even if it kills him. At night, he ascends to the attic and the large radio he has kept hidden and recites numbers and locations of Nazi sites for the resistance. Afterward, before signing off, for a few minutes he reads old scripts that he and his brother had written before the war, scripts about science and wonder intended for children, for the very same recordings that captivated Werner when he was a boy. Uncle Etienne sees the world around him, bereft of those he loves, save his niece, and realizes that he cannot simply sit while the world flies by. And so he speaks, softly, and he tells the world of wonder and joy and the mystery and beauty of the eye’s ability to perceive light. This dedication to even the smallest resistance through knowledge, science, and human connection becomes a candle with which to keep the hope in their house, and their city, alive.

Those very elements are what bring Signe to the devastated and blasted ruins of Voortyashtan, the decrepit city that once guarded the river into the heart of the Continent, and is now choked with eighty years of war and rubble. An innovator and inventor, Signe—for all she lacks in social graces—understands the importance of her project; through the cleaning of the river and the new city above it, they would not only bring industry back to the area, they’d bring the rest of the Continent back to the city. Her belief in science and technology, in bridging the gap between what is and what may be, acts as a post-war answer to the horrors that came in the years before she was born. Her relationship with her father, an old soldier himself who has such a hard time relating to her and what she hopes to accomplish, serves to further explore the connection between one generation and the next.

Finally, while there is so much more to unpack in these books, perhaps the biggest preoccupation shared between these novels is the supreme importance of choosing your narrative. Voortya, the goddess of war, watched over her people with a mighty eye and twisted them into her weapons, her demons, her soldiers, who razed cities and burned those who were different from them. And Hitler and the Nazi Party did much the same thing, using charisma, power, and fear to take a people and turn them into the dictator’s personal weapon. He and his cronies built a warped and paranoid national narrative and constructed a mythos that fed into that fear and that thirst for power. As evidenced by both the Nazi war machine and the Sentinels of Voortya, these narratives strip away humanity and compassion, leaving only cruelty and violence in the hearts of their followers. It isn’t until the exposure to different kinds of narratives that Werner and the Sentinels can recover themselves.

Trapped in a hotel under bombardment, desperate for air, food, and light, Werner clings to his radio and finds, of all things, Uncle Etienne’s radio signal. Except it’s Marie Laure, and she’s reading the final act of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. Enraptured, Werner dives into the story with her as she reads, and they both head down into the lightless deep; Werner is trapped, while at the same time someone is stalking through Marie Laure’s home, desperate for something she possesses. The narrative of the great unknown, of a new world, of people working together to find wonder is finally what pushes through to Werner, and with a new vigor he begins to realize what he’s done, and what he has to do. A new story breaks through the tale he’s been told for so long, and taking inspiration from it, he can finally venture out to try and do some good.

Likewise, Mulaghesh finds herself before a horde of super-powered Divine Sentinels, ready to raze the Continent and fulfill the promises of their dead goddess. (Without getting into heavy spoilers) Mulaghesh finds herself confronted with a question, and the answer matters more than worlds: what is the purpose of a soldier? And after a life’s worth of bitterness and cynicism, of giving into easy worldviews where the strong prey on the weak, Mulaghesh has to dig deep and dredge up that guttering spark of hope in her that grows stronger every time she sees a soldier act out of goodness than fear. Hope tells her that a soldier is one who protects and serves and doesn’t harm unless in that defense. To be a soldier is to put your heart and your very self on the line, to die rather than kill. And in the moment when she comes to that realization, the narrative changes, and the idea of being a soldier is opened to greater possibilities, beyond the narrow definition everyone has been repeating since the beginning of the book, and she is given a chance to be something different and better.

Stories matter. The truths we tell ourselves sink into our bones, push our bodies ahead, urge our blood to sing. These stories are the bridges between the worlds of people, and if enough people tell the same story, it can become true. Both of these stories are concerned with war, yes, and pain and violence and trauma. But in the end, both books are concerned with not just the reality of the war, but the way one can move on from it. That a rose can be redeemed from thorns. That there are, if not happy endings, then good ones, noble ones, honorable ones. That you can face your ghosts, and see a future where they don’t haunt you.

All the Light We Cannot See and City of Blades are so powerful and resonant because they offer the one thing most needed at the end of the war, when the smoke is clearing and something is visible just outside lights of the horizon.

They offer hope after pain.

And there is no nobler effort than that, in any story or world.

Martin Cahill would like to hire Mulaghesh as his professional life coach and drinking partner. When he’s not slinging words at Tor.com, he’s contributing to Book Riot and Strange Horizons, writing his own blog, Craft Books, and endlessly revising a novel he wrote. You can find him on Twitter @McflyCahill90. Tweet him about delicious stouts, ideas on who Rey’s parents are, and your worries about the DC Movie Universe.